Posted 1/13/2020

In the post-WWII era, the U.S.’s manufacturing economy was booming. Industries like steel, copper and mining employed huge numbers of workers — and small towns with factories, mills or mines proved vibrant.

But by the mid-1970s, the economy had shifted. Technology, coupled with shipping jobs abroad, had gradually changed the landscape. And those once-prosperous communities eventually fell into decay.

Such is the backdrop to Samuel D. Hunter’s Greater Clements, now at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater. In the tiny mining town of Clements, Idaho, Maggie (Judith Ivey) and her mentally ill son Joe (Edmund Donovan) eke out a precarious living giving mining tours. But the town, which just unincorporated, is a wasteland of woes, and its future is bleak.

The decision to become unincorporated means there are no street lamps at night, an apt metaphor for the darkness — internal and external — that haunts the characters. Even in its heyday, mining was a dangerous, ill-paid job — and Clements’ miners often paid the ultimate price.

Is there hope for those caught in the aftermath

of economic despair?

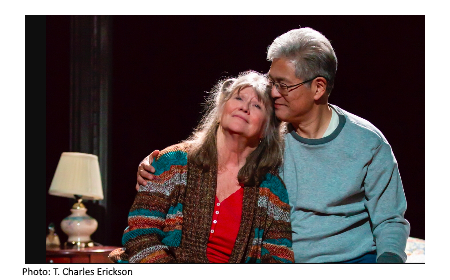

In Maggie’s case, lost love may prove redemptive. Billy (Ken Narasaki),

her teenage boyfriend, reappears after 50 years. Billy is saddled with

his own issues, but he’s clear on one thing: He wants a life with

Maggie.

Maggie and Billy each carry emotional baggage, and both are responsible for others. Joe’s problems are deep; there are no easy fixes. Billy is caring for Kel (Haley Sakamoto), a troubled 14-year-old granddaughter from a broken home. Happiness eludes everyone; they settle rather than aspire.

Hunter’s nearly three-hour play examines the underbelly of small-town life: sex, violence and personal secrets that haunt its citizenry. The pathos is real, so are the emotional constrictions that sadly limit their options for happiness. The question is: Can anyone break the cycle?

Ivey’s nuanced performance fills the stage — she runs the gamut of emotions, from devastation to joy — and is compelling to watch. Donovan astoundingly captures all the pain of the tortured, but adds a strange tenderness all his own. Sakamoto imbues Kell with layers; yet Greater Clements ensures that no one escapes unscathed.

While the cast is solid, the story’s trajectory is less so. The ending is predictable and, given the characters’ histories, inevitable. The West may appear as a vast land of rugged individuals in American mythology, but here, it’s the smallness of lives that resonates.

For those who prefer tragedy on a more fanciful scale, one of the most popular and beautiful ballets, Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, will be performed by the Shanghai Ballet at the Koch Theater, Lincoln Center, January 17-19. Boasting 48 balletic swans on stage, the production is directed by Derek Deane, the former artistic director of the English National Ballet.

The New York City Ballet Orchestra accompanies Deane’s Grand Swan Lake.

The story, inspired by Russian and German folk stories, is the tragic love story of Prince Siegfried and Princess Odette, who is transformed into a swan by an evil sorcerer.

Shanghai Ballet, under the direction of Xin Lili, is noted for blending traditional and Western dance styles. Playing to global audiences, its ballets include Swan Lake, Jane Eyre and The Last Mission of Marco Polo, as well as its specific version of The Nutcracker.

Swan Lake stars principal dancers Wu Husheng and Qi Bingxue; some 80 dancers in total will participate in this exquisite ballet. —Fern Siegel