(

The Confession of Lily Dare, Paddington Gets In A Jam

The Big Apple Circus, Aesop’s Fables

Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow

The Rolling Stone, DogMan The Musical

The Secret Life of Bees, Monday Night Magic

Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus

Be More Chill, Merrily We Roll Along

The Prom, Circus Abyssinia: Ethiopian Dreams

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Big Apple Circus

Happy Birthday, Wanda June, Apologia

Head Over Heels, Straight White Men

Secret Life Of Humans, Tchaikovsky-None But The Lonely Heart

The revival of My Fair Lady is, in a word, perfection.

Lincoln Center’s production of Lerner & Loewe’s classic musical, the first Broadway revival in 25 years, is visually dazzling. The Vivian Beaumont is the ideal forum — large, yet intimate — to showcase this lush production.

Alan Jay Lerner’s tart book underscores G.B. Shaw’s concerns about gender equality, class and the inherent prejudices of the patriarchy. Director Bartlett Sher has crisply restaged the beloved musical, making it as relevant to the #MeToo generation as it was to the post-war audience, when it debuted in 1956.

Lauren Ambrose who gives an astounding performance as Eliza Doolittle, the spirited Covent Garden flower girl, is determined and heartfelt. And then there is her voice.

Who knew this accomplished dramatic actress (Awake and Sing!) could sing so beautifully?

My Fair Lady is based on the 1938 filmed version of Shaw’s play Pygmalion, itself inspired by the Greek myth of Galatea, the ivory statue that comes to life. Eliza’s evolution — the ignorant daughter of an indifferent drunk (a spunky Norbert Leo Butz) transformed into a woman who can pass as a highborn lady — is a clever thematic device.

That transformation is the handiwork of Professor Henry Higgins (a marvelous Harry Hadden-Paton). Of course, it is Eliza who seeks out Higgins. He sees her as a social experiment, betting a fellow linguist, Colonel Pickering (Allan Corduner), he can transform a “guttersnipe” into a highborn lady. To Higgins, anyone can acquire the trappings of society, if they mimic voice and bearing. The distinction is strictly external.

Higgins may deem himself an egalitarian — “I treat everyone the same” — but he is devoid of sensitivity, a shell of a man pretending to be whole. Under Eliza’s tutelage, he manages some growth, which is remarkable given his bullying arrogance.

Conversely, Eliza is the total package — a flower girl with the soul of a lady — true class being internal. He feels entitled; she has to earn her place. (A reality that still speaks to 21st-century women.) Their polarity is neatly underscored by Lerner’s famed lyrics, augmented by Loewe’s gorgeous melodies.

The show is sprawling — from Covent Garden to Ascot — and set designer Michael Yeargan captures 1913 London impeccably. A hint of reform is in the air, even with an entrenched class system. Catherine Zuber’s gowns are exquisite — the Ascot hats pull out all the stops.

Ambrose and Hadden-Paton share a chemistry that’s a joy to watch — especially since it’s nuanced. And Diana Rigg as Higgins’ all-knowing mother is a theatrical treat.

My Fair Lady is a difficult show to stage; the expense is considerable and the actors, in every role, must be exactly right. Sher has scored on all fronts. He and his stellar cast have honored Shaw’s vision with style.

For a truly European experience, consider Pss Pss at the New Victory.

Two talented performers, Camilla Pessi and Simone Fassari, have created a whimsical 65-minute show that’s perfect for young children. Paying homage to Chaplin, Keaton and Marcel Marceau, they employ an impressive array of flips, acrobatics and various absurdist antics that prove hypnotic.

And though they never speak, they have a lot to say.

The trick is in the timing — they are sensitive to moment and build the act organically. Trained as circus performers, they can convey moments of hilarity or tenderness just by a simple bow or the flick of a finger. Imagine a Beckett duo in a silent Italian film, accompanied by accordion music with a distinctly Spanish timber.

Singular and funny, Pss Pss’ simplicity is utterly charming. —Fern Siegel

Torment is often a fertile breeding ground for art.

And it was the impetus behind many of the acclaimed works of Tennessee Williams and William Inge.

But in 1944, before either became giants in the theater, they met in St. Louis. Inge was a journalist interviewing Williams, just prior to the staging of A Glass Menagerie in Chicago.

Literary historians suggest they became lovers, and Williams was helpful in encouraging Inge’s career as a playwright. But what happened at that fateful meeting before fame and critics engulfed them?

That’s left to the vivid imagination of Philip Dawkins, who has fashioned an entertaining, highly charged, deeply evocative play aptly titled The Gentleman Caller, now off-Broadway at the perfect venue, The Cherry Lane.

Juan Francisco Villa is an ideal Williams, capturing his charm, vulgarity and poetic sensibilities with élan. The sensual Williams is all id. By contrast, Inge (Daniel K. Isaac) is a conflicted loner, far too reliant on alcohol and despair.

Williams shares his anxieties about the upcoming Menagerie production, though Inge has yet to read his play. When he attends its debut, his vision of theatrical and personal possibilities is forever transformed.

The Gentleman Caller deftly explores the power of sex, desire and suffering — and how it can shape destiny. Williams parlays his emotions and familial pain into art; it’s theater as biography. Inge also took elements of his upbringing and a repressive Midwest ethos and turned it into Picnic and Come Back, Little Sheba.

While neither man can claim happiness, Williams in Gentleman Caller clearly has a lust for life that Inge can only envy. Yet watching these polar opposites struggle for connection proves a devastating and captivating two hours.

The catch in an otherwise superb production, including an intriguing set design by Sara C. Walsh, is the casting of Isaac. Nontraditional casting can work in fictional settings, but it’s a jarring choice for real life. Especially when Villa looks and acts exactly like Williams. Does Inge deserve any less?

Moreover, Isaac takes too long to get into Inge’s skin, and he never seems comfortable in his role, whereas Villa relishes his. Still, Dawkins’s script — a memory play that pays homage to that virtue in Glass Menagerie — is beautifully written. It salutes two creative souls who, ironically, helped define post-war American drama, even if they could not please themselves. —Fern Siegel

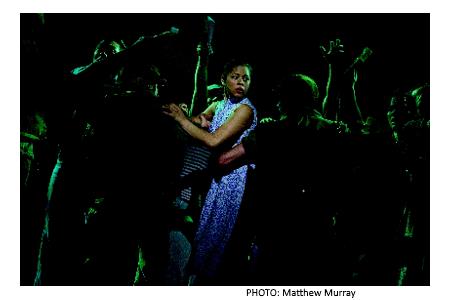

The Harry Potter books were a global sensation. And the movies gave an exciting visual dimension to the hypnotic world of Hogwarts. Remarkably, the Broadway incarnation at the Lyric — Harry Potter and The Cursed Child, Parts I and II, adds its own magical twist — and it’s nothing short of eye-popping.

Even the Lyric Theatre has been revamped, including the carpet — emblazoned with the Hogwarts crest.

John Thorne’s new play, based on an original J.K. Rowling, Thorne and John Tiffany story, is a worthy addition to the canon. It takes place 19 years after the saga’s finale. But it is director John Tiffany’s spectacular stagecraft — bookcases came alive, portraits talk and Dementers swarm — that makes this five-hour, two-part production memorable.

Many of the beloved Potter characters are in attendance, as are some notable new ones. (It’s a 40-person cast.) The Cursed Child continues the adventures of Harry, Hermoine, Ron (Paul Thornley) and Draco Malfoy (Alex Price). Only this round, the focus is on the next generation.

Harry (Jamie Parker) and Hermoine (Noma Dumezweni) run the Ministry of Magic — and remain ever vigilant for any signs of evil. But like all parents, Harry must deal with the vagaries of adolescence, in this case, his rebellious son Albus (Sam Clemmett) and Scorpius Malfoy (Anthony Boyle).

The Harry Potter books dealt with parent-child issues, in all their touching and frustrating iterations. Here, it is kicked up a notch.

And it’s against that father-son backdrop, with a new legion of eager wizards, that the story unfolds. In essence, The Cursed Child is an interesting meditation on time, circumstance and expectation.

Part of Rowlings’ ethos is that people have to make crucial decisions about how they choose to live – and with whom they choose to share their lives. Alongside familiar elements are unexpected and astounding ones.

The music by Imogen Heap and movement by Steven Hoggett are amazing. So is the artistry of Christine Jones’ sets, Katrina Lindsay’s costumes and Gareth Fry’s sound design. The show is a technical triumph.

The cast clicks, especially the chemistry between Boyle and Clemment.

In fact, the play is so cleverly written, audiences must see both parts. Harry Potter and the Cursed Child offers moving, as well as show-stopping moments. Billed as “the eighth Harry Potter story,” it is a must-see for fans.

The Rainmaker at the Sheen Center offers off-Broadway a different kind of “magic.” Set in the West in 1928 during a drought, the action takes place over a day.

The 100-degree heat hasn’t just caused cattle to die; it’s also dried up hope and the possibility of love and friendship.

The Curry family is experiencing it’s own drought of self-belief. An affable father (Ken Trammell), his son Noah (Benjamin Jones), who runs the ranch, and younger son Jimmy (Sean Clearly), enamored of the town’s party girl, worry about their sister Lizzy (Fleur Alys Dobbins), dismissed as a spinster.

Even her well-intentioned brothers falter when advising her to “get a man the way a man get got!”

The play’s themes — the nature of truth and the value of dreams — are kick-started with the arrival of a stranger called Starbuck (Matthew Provenza).

He is a handsome, fast-talking drifter whose specialty is selling hope. In this case, promising to bring rain to the barren town. Now, con men and snake-oil salesman have long been part of the American landscape. Are they believed out of desperation? Or do we put common sense aside for the slimmest chance of rescue?

Here, Starbuck is a catalyst — and the shifting allegiances prove both dramatic and poignant.

This sensitive revival of playwright N. Richard Nash 1954 hit is well served by Sheryl Lu’s sets, a first-rate cast and Dobbins’ nuanced performance. Provenza is ideal for the role, while Jones’ Noah nicely captures the concerns and occasional oversteps of the dutiful son.

The Blackfriars Repertory Theatre has a mission: It seeks plays that reflect “the spiritual nature of man and his eternal destiny.” It has scored with this version of The Rainmaker. —Fern Siegel

There is nothing like a literary scandal to kick-start a sassy playwright. Such was the case with Alexis Piron, the 18th-century writer who produced La Metromanie (meaning crazy for poetry), which includes a send-up of the famed writer/philosopher Voltaire.

Voltaire, author of Candide, had claimed a great love for an unseen poetess. She turned out to be a he — and Voltaire was publicly embarrassed. Piron was delighted and alluded to the story in La Metromanie. Centuries later, David Ives, brilliant at updating French farce (The Liar, The Heir Apparent), added his own twist.

The result is the witty and zesty Metromaniacs, now off-Broadway at The Duke. The latest of Ives’ “translaptations,” the play, set in Paris in 1738, boasts false identities, confused lovers, feuds and fun.

The Red Bull Theater’s production is silly yet zingy, thanks to Michael Kahn’s lively direction, Murell Horton's costumes and a cast that glitters — all rendered in iambic verse, an Ives’ specialty.

The Metromaniacs opens at the home of Francalou (Adam LeFevre), with a room transformed into a leafy glen. The painted trees amid chandeliers are pretty and underscore a larger point: Everything is artifice; so just enjoy it.

Both Francalou and his lovely, sought-after daughter Lucille (Amelia Pedlow), are mad for poetry. She is courted by two men: Damis (Christian Conn) and Dorante (Noah Averbach-Katz.) Lucille can be as capricious as her maid Lisette (Dina Thomas) is earthy.

For reasons known only to French farce, the men cannot tell the women apart, since Lisette has a habit of dressing like her mistress. Then again, the plot, such as it is, is secondary. The real fun is watching these seven characters, including the servant Mondor (Adam Green) and Francalou’s old foe Baliveau (Peter Kybart), claim their romantic prizes.

Ives’ inventive rhymes amaze. His social commentary speaks to every age. The nonstop couplets propel the action, climaxing in an entertaining finale.

Two doors away, the Broadway revival of Tom Stoppard’s Travesties at the American Airlines Theater, takes cleverness a step further. Known for his intellectual banter and ruminations, Stoppard supplies a sassy diatribe on history, sans a traditional through line.

The setting is the Zurich Library in 1917, during WWI, teeming with refugees, spies and artists of every stripe.

James Joyce (Peter McDonald) is writing

Ulysses; Lenin (Dan Butler) is compiling his treatise on

imperialism, waiting to join the Russian Revolution; and Tristan

Tzara (Seth Numrich), cofounder of Dadaism, is espousing his belief

in the nonsensical.

All are set against the backdrop of a reimagined version of Oscar

Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest. That means an informed

Cecily (Sara Topham) and Gwendolen (Scarlett Strallen) make notable

appearances.

Center stage is busy — and the action, such as it is, is narrated by Henry Carr, a British consul (a fantastically versatile Tom Hollander). The overarching theme is the place of art in society.

Can art affect social change? Is it a purely creative endeavor? Or does it simply indulge the fancies of its creators? The big movement of the era, Dada, often called “anti-art” in its quest to destroy artistic conventions, is examined with a whimsical and critical eye.

Travesties is a memory play – with all its imperfections — moving back and forth in time. That’s part of the play’s charm, as is Stoppard’s singular approach to war, literature, politics and love. The word “travesties,” which actually means “ a distorted representation,” tackles such questionable representations of historic and literary figures — all with his provocative wordplay.

Aided by Tim Hatley’s sets and costumes, Neil Austin’s lighting and Adam Cork’s sound design, the Roundabout’s revival is artistic and engaging. Thank the inspired direction of Patrick Marber and his stellar ensemble, led by an engaging Hollander, which doesn’t miss a beat.

Stoppard is not always the most accessible playwright, but among the most interesting. —Fern Siegel

There is a powerhouse on Broadway — and her name is Glenda Jackson. The revival of Three Tall Women at the Golden Theatre is blessed with her presence. Absent for decades, due to a political career in Britain, the Oscar winner has returned in triumph.

The three women of the title, known only as A, B and C (Jackson, the great Laurie Metcalf and Alison Pill) play three separate characters — ages 26, 52 and 91.

Edward Albee’s play is assumed, in part, to be a look at his relationship with a difficult mother. Jackson plays the cranky, imperious elder with the air of a socialite torn between the impulse to dictate and the crippling horror of dependency. It is astounding to watch.

More telling, the women eventually morph into three manifestations of a single self. The trio is less a triangle than an evolution, the making — and unmaking — of a woman at various stages of her life.

And that’s where the play, under Joe Mantello’s careful direction, gets interesting.

Miriam Buether’s sets set the right note of formality, as does Paul Gallo’s lighting. The accomplished cast dissects the subtleties and exasperations of age with surgical precision.

A look at life, death and the myriad circumstances that shape us, Three Women is as heartbreaking as it is revelatory.

Carousel is also noteworthy — but for far different reasons.

The Rodgers & Hammerstein musical revival, now at the Imperial Theatre, first debuted on Broadway in 1945, an adaptation of Ferenc Molnár’s turn-of-the-century story. Transferred to a coastal town in Maine, it follows the doomed relationship of brutal Billy Bigelow (Joshua Henry) and sweet factory girl Julie Jordan (Tony winner Jesse Mueller).

While the score is beautiful — including now famous songs, such as “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” sung by the stellar Renee Fleming, “If I Loved You” and “June Is Bustin’ Out All Over,” the plot is problematic at best.

From inception, it’s hard to see Julie’s attraction to the coarse carnival barker, yet the two soon marry.

Billy is out of work — and takes out his frustrations on Julie. The townspeople and her best friend Carrie (Lindsay Mendez) are horrified that he beats her. He’s quick to amend: “I only hit her.” In the #MeToo era, that’s not only a hideous justification, it’s cringe worthy.

Equally disturbing, are the domestic rationalizations Julie is forced to utter — “He’s unhappy ’cause he ain’t working.” That’s accompanied by the disturbing lyrics of “What’s the Use of Wond’rin?”

Which underscores a larger point: Is Carousel, with its toxic masculinity, a musical worth reviving? Even when Billy has a chance to redeem himself, he stumbles.

Yes, the leads have glorious voices, and Joshua Henry delivers a super-powerful “Soliloquy” to end act one. Santo Loquasto’s spot-on sets are evocative, especially the exquisite carousel that opens the show. The lighting by Brian MacDevitt, along with Ann Roth’s costumes, set the stage perfectly. Justin Peck’s choreography is highly balletic.

But you know you’re in trouble when the leads have little chemistry and the feature players upstage the stars.

More ironic, Mueller’s last Broadway show, Waitress, posited an abused wife who summons the strength to leave her husband. Carousel’s Julie leaves the talented actress little room to maneuver.

So how do 2018 audiences approach Carousel? The real joy is the many memorable songs, which could easily be revamped as a City Center “Encore” production of R&H’s best efforts.

But to restage without director Jack O’Brien giving it a fresh perspective suggests the musical has taken its last ride. —Fern Siegel

Identity is fertile ground for drama, but disassociation kicks it up a notch. Or as our narrator explains: “I’ve gotten on a ride I can’t get off.” And it’s a wild one.

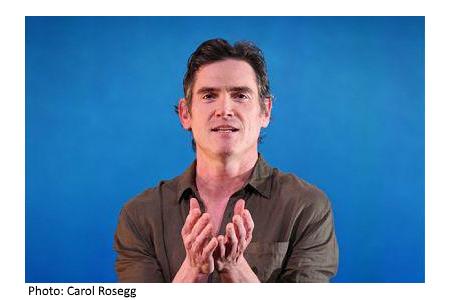

The narrator is Billy Crudup — and for 80 minutes at the Minetta Lane Theatre in Harry Clarke, he holds us in his thrall.

In fact, the play opens with: “I’m Harry Clarke, and I’m gonna mess you up.” That’s less threatening when you consider the source: an 8-year-old Midwesterner painfully at odds with his environment.

Harry, whose real name is Philip Brugglestein, is a poster boy for fractured identity. To cope with an abusive, homophobic father and the early death of his mother, he transforms himself.

By adopting an English accent by way of PBS, sometimes “Britey Brit,” more often Cockney, which drives his father mad, he becomes Harry Clarke, a convenient out for a shy, lonely kid. So powerful is the lure of a second self, that even the threat of electroshock therapy can’t dissuade Philip from his invention.

Which is why at 18, he finds himself headed to the sacred refuge of all outsiders: New York City. And there, over time, Harry Clarke comes into sharper focus.

Philip may not have the guts to grab what he wants, but Harry does. Philip is insecure; Harry is cocky and aggressive. And Harry can think on his feet – inventing a colorful career as tour manager/assistant to pop singer Sade and hoodwinking Mark Schmidt, a rich troubled guy, and his equally needy family.

Playwright David Cale is interested in how

people navigate their place in a social world. Harry Clarke is a

thoughtful, entertaining look at disassociation that asks primal

questions about existence: Who are you? What is really true: the

authentic self or the alter ego?

Coast of Utopia Tony winner Crudup, who can be rough and sexy in one

turn, and scared and disarming the next, delivers a remarkably

muscular performance, directed by Leigh Silverman. Doing 19 voices,

young and old, gay and straight, male and female, he fully inhabits

each character. Some are just brushstrokes, others main events — all

are delivered with ease and virtuosity.

Cale previously wrote and performed acclaimed solo plays The Redthroats and Lillian. This round, he decided Crudup could do it better.

The problem is that while Crudup is sensational, the play is not. There are some surprising twists and turns, assuming we can believe Harry’s narrative, but its engagement factor is limited. False bravado can only carry an audience so far.

In common parlance, Harry is a trickster, a con man. But the biggest con may be on him. —Fern Siegel

A circle of electric fans, two suitcases, balloons, helium and two primary colors are all it takes for the endlessly inventive Arcobuffos, husband-and-wife team Seth Bloom and Christina Gelsone, to mesmerize an audience for an hour.

With a knack for balancing high art and vaudevillian laughs, AirPlay, now at the New Victory Theater, is a delightful exploration of physics, comedy and surprise. The production takes atmospheric changes literally.

By the show’s end, the audience marvels at how something as simple as gravity and wind can be turned into such an awe-inspiring display. The oohs, aahs and giggles are nonstop.

Air Play not only employs the elements, but toys with the limits of the theater space itself, sending silk ribbons out over the audience and floating balloons up to the ceiling.

At the same time, the show finds emotional depth in the intimacy of

two performers sitting side by side at the edge of the stage. The

exploration of light and heavy, up and down, large and small, is

constantly in play.

The sculptural creativity is thanks to Daniel Wurtzel, with poetic direction by West Hyler. Whimsical and ethereal, Air Play captivates all ages.

Also geared to kids, but with a big Broadway showcase, Frozen, now at the St. James, offers a feminist twist on standard fairy-tale fare.

The struggle here isn’t between good and evil or predicated on the enduring sexism of female rescue. For as movie fans already know, the handsome prince is anything but a good guy.

The real focus is Princess Elsa (a glittering

Caissie Levy), who wrestles with her own demons and icy powers. The

glorious element of the story is the enduring friendship between the

sisters, Elsa and a comic Princess Anna (a spunky Patti Murin).

The women have to rely on each other to save themselves and their

kingdom. Translation: girl power!

Of course, the stage offers challenges to the cinematic version, but the creative team acquits itself imaginatively. The lighting by Natasha Katz is lovely and Christopher Oram’s stylized sets hit the mark, augmented by Michael Grandage’s zippy direction and Rob Ashford’s lively choreography.

The Broadway production adds about 12 new songs, in addition to the movie score, with music by Kristen Anderson-Lopez and Robert Lopez. All enhance the original experience, as does a strong ensemble cast.

Frozen’s overarching theme — that love can set one free — is compelling. And for kids, especially girls, the movie’s original target, that’s a liberating premise. But the big wow factor theater-wise is Levy’s dramatic and moving performance. Her act one showstopper brings down the house. —Fern Siegel

For fans of classic rock and classical genres, Broadway’s Rocktopia, co-created by Rob Evan and Randall Craig Fleischer at the Broadway Theater, is a unique music experience. Mozart, Queen, Beethoven, U2, Tchaikovsky, Pink Floyd and The Who are among those showcased.

But be prepared for the shattering sound volume and the concert’s template: Classical selections are often intros to rock, and/or can be heard beneath the pounding rock beat.

Hearing classic songs, such as “Kashmir” and “We Are The Champions” played with a full orchestra surpasses the standard guitar/base/drums/piano set-up. The show opens with Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra” (best known from 2001: A Space Odyssey) leading into The Who’s “Baba O'Riley.”

The 62-person company includes singers Chloe Lowery, Tony Vincent, Kimberly Nichole and Alyson Cambridge, as well as accomplished musicians.

The result is a mash-up of classic rock with what the creators believe is similarly themed classical music pieces. Hearing 18th- and 19th-century compositions next to and sometimes intertwined with modern melodies — Mozart’s “Eine kleine Nachtmusik” with Styx’s “Come Sail Away,” Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique” with Aerosmith’s “Dream On” — illustrates a valuable point.

Musical delivery has changed, but the emotions generated by music — love, rebellion, joy — are timeless.

On stage, the singers were solid, though

Cambridge and Lowery had the most powerful pipes. Their rendition of

classical opera and big hits, such as “I Want To Know What Love Is”

showcased their talent.

Temporary artist Grammy-winning Pat Monahan was also exceptional and

getting to see him perform his Grammy-winning “Drops of Jupiter”

with the full orchestra is notable. Mairead Nesbitt’s performance as

violin soloist was masterful. She seemingly flowed around the stage,

while occasionally getting into cross-time riff duels with lead

guitarist Tony Bruno.

Austin Switser's video content in the background helped enunciate the musical themes but occasionally distracted from the performers on stage. Michael Stiller's lighting design is the typical concert experience, with the exception of the encore performance of “Bohemian Rhapsody.”

However, it would be helpful to move Rob Evan's introduction/explanation of the show from right before the end to right after the opening montage. It’s an important framework, even if there are legit quibbles about overall effectiveness.

True, there are some Las Vegas moments in costume and some iffy song associations, but for fans of crazy musical mash-ups, especially millennials, this could be their ticket. —Fern Siegel

The Public Theater has had a bit of success lately with the American Revolution. So it should be no surprise that Bruce Norris’ The Low Road, a political satire about the price of free enterprise set during our country’s bloody birth, has been swaddled in a handsome production at the Public’s Anspacher Theater.

But be forewarned; there is something nasty in the nursery.

Norris, who won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Clybourne Park, has written a show that conceals an intrinsically dark legacy, belying its cosmetic resemblance to a rollicking period romp. The play’s kinship is not to Henry Fielding's exuberant novels, but more akin to an Ayn Rand revision of Candide.

The Low Road, set in the mid-18th century, is actually minted in the currency of 2018. Our guide down is the Scottish moral philosopher, father of free-market economics and champion of self-interest Adam Smith (tartly played by Daniel Davis).

Smith is the inverse of Voltaire's paragon of optimism, Dr. Pangloss; he’s a detached rationalist who coolly observes a pack of rats devouring each other as he readies a pinch of snuff.

The story revolves around young Jim Trewitt (Chris Perfetti). We first meet him as a foundling (and rumored progeny of a certain "G. Washington”), left in a basket on the doorstep of mildewed madam Mrs. Trewitt (the inestimably inventive Harriet Harris).

The enterprising lad, via a happenstance encounter with Adam Smith's opus The Wealth of Nations, is guided by self-interest and greed. Jim quickly learns how to collect the wages of sin on behalf of Mrs. Trewitt's residents, while redistributing a fair portion of the proceeds into his own pocket.

He’s willing to cheat prostitutes, an educated slave (Chukwudi Iwuji) and a decent businessman (Kevin Chamberlin).

Thus begins a life fatalistically built on Smith's precepts. The pimp-industrialist is merely a stand-in for Martin Shkreli in period frock, inflating the price of prostitutes instead of vital AIDS medications. All the while, our interlocutor adroitly serves as a narrative bridge between our contemporary sensibility and the colonial shenanigans of Low Road.

By creating a protagonist who is an assemblage of appetites with no discernible inner life or capacity for self-awareness there is no learning, evolution or recognition for this character, only repetitive behavior. (And yes, the parallels to Donald Trump are all too clear.)

Instead, we have a secondary protagonist in the form of fugitive slave John Blanke, named after the signatory line on his contract of ownership. The inverse of Trewitt, Blanke reveals himself to have the soul of a tortured and self-aware artist.

The miraculously graceful performance of Chukwudi Iwuji gives us the feast of a character's inner life and conflict, in contrast to the unsatisfyingly narrow consciousness of Trewitt.

Iwuki’s valiant performance is the human core of the story.

Eventually, he finds his way into the hearts of the Lows, a liberal society family devastatingly played by the astonishingly versatile trio of Chamberlain, Harris and Tessa Albertson.

Despite the sometimes-meandering polemic, there are genuine plusses here, including the accomplished stagecraft by director Michael Greif and the fine ensemble performances.

Also of note, the splendid costumes by Emily Rebholz and a plethora of wigs by J. Jarad Janas and Dave Bova establish another time and place in the blink of an eye.

The play is marinated in irony, a difficult tone to maintain in so sprawling a story. As a result, it's often clever instead of affecting and provocative rather than insightful.

Still, The Low Road is an impressive effort, despite its bleakly cynical subterranean current. That’s due to Norris' diagnosis of our own 21st century economic disparity and class structure, our inescapable inheritance from England. —Fern Siegel

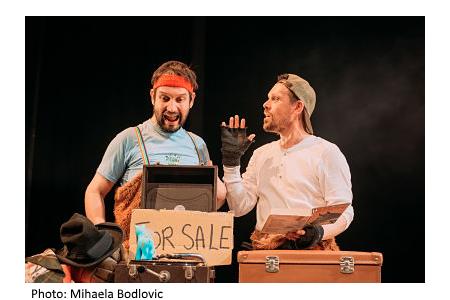

It’s not easy being the front and back of a pantomime horse named Hamish. That’s the life of Older Andy (Andy Cannon) and Wee Andy (Andy Manley), the wacky, down-and-out McCuddy brothers who live in a trailer in Britain.

To keep financially afloat, they decide to sell their possessions at a yard sale — and that’s when they find a copy of Black Beauty.

The discovery kicks off a humorous, unconventional telling of the famed novel Black Beauty, now off-Broadway at The New Victory Theater. Both Andys (“a family thing”) are a bit goofy and worried about the future. But to keep their spirits up, the duo assemble various props to act out Anna Sewell’s beloved 1877 tale.

Their inventiveness proves entertaining for the young audience. Shoeboxes are a stable, while shoes double as horses: high-heels for Ginger, a baby shoe for Merrylegs and a black rain boot for the eponymous Black Beauty.

The men play all the characters, even

throwing in some fun word play, like “ginger snaps.”

But don’t go expecting a literal recreation of the Black Beauty

story. For those who read the book, the more serious (and troubling)

aspects of the original narrative are missing. Children 4 to 6 will

enjoy the absurdity; the savvier 8+ might favor a little more

detail, though all will embrace the entertainment.

The sound design and lighting nicely augment the production, which boasts clever improv moments. The revamped narrative is solid and the audience participation is a plus. While the core plot steers away from the traditional equine story and more toward the brothers’ lives, it’s punctuated with an important underlying lesson: Never give up.

The sweet show was cocreated, cowritten and performed by Cannon and Manley, with Shona Reppe as cocreator and designer. Dave Trouton and Simon Wilkinson are the evocative sound and lighting designers, respectively.

Reenacting various parts of Black Beauty provides solace for the two Andys — while reminding its audience that necessity is the mother of invention — and creative satisfaction. — Fern Siegel

A show of hands for anyone who thinks Washington lobbyists corrupt public policy? That’s the Kings audience. Though spot-on in its commentary, the play, now off-Broadway at the Public Theater, is preaching to the choir.

Sarah Burgess’100-minute effort does make key points — lobbyists who represent corporate interests rather than the American people undermine sound public policy.

Plus, it has a stifling effect on our

representatives.

At a time when the NRA decides U.S. gun policy, Kings resonates.

Trump may trumpet his immunity from influence, but his policy

decisions suggest otherwise — be it mining on once-preserved

government lands or backtracking on sane gun control.

As Kings notes, Congress spends most of its time at fundraisers; actual governance can be secondary, often dictated by powerful lobbyists. Thus, when it comes to Congressional reps or U.S. senators, it is understood that lobbyists like Kate (Gillian Jacobs) and Lauren (Aya Cash) don’t waste time on the unelectable.

And to stay in office, reps play ball.

So what happens when maverick Sydney Millsap (Eisa Davis), who refuses to compromise, arrives in Washington D.C.? Her savvy pitch — she’ll take lobbyists’ money but not grant them time or favors — is refreshing. The seasoned hacks, conversely, deem her crazy.

Ideologically pure neophytes don’t know the score, explains arch, power lesbian Lauren — a point made throughout. She only supports winners, like Sen. McDowell (Zach Grenier), who does corporate America’s bidding. As for Kate, she’s hedging her bets. Given Millsap’s relentless honesty, she may be forced to confront her own cynicism.

Burgess is adept at taking on specific arenas. She also wrote Dry Powder, performed at the Public two years ago. A nuanced play about private equity that found humor in the intensely competitive elements of American capitalism, Dry Powder showed financiers so removed from daily life that people and things were reduced to numbers on a balance sheet.

Similarly, Kings reduces democracy to a system in which corporations choose our officials. If the public thinks it selects their reps, they are woefully naïve. Burgess makes that well-trodden point in an entertaining way.

Cash’s Lauren is solid; venomous in her tight, amoral approach to politics, while Jacobs calibrates cordiality. Davis’ matter-of-fact approach is appealing in a quixotic way, while Grenier nails the self-justifying long-term senator. Director Thomas Kail, working on a small stage, augments Kings’ message by sitting reps and lobbyists at a revolving table. They go round and round in circles — which sums up the obvious: There is no breakout star that bucks the system. There is only hope — until fake news and that deadliest of weapons, social media, are enlisted to finish what lobbyists started: destroy majority rule.

—Fern Siegel

It’s fitting that the divine Ute Lemper’s latest cabaret show is Rendezvous With Marlene, as she shares several key traits with Hollywood legend Marlene Dietrich. Both are captivating performers who harbored conflicted feelings about Germany, their birthplace.

And both are strong, sultry, alluring women with singular careers.

Thus, in the elegant Café Carlyle through March 3, Lemper, acclaimed internationally as an actress and singer, pays an emotional musical tribute to Dietrich, one of the stars of the Weimar. (Lemper made a name for herself singing the Weimar repertoire.)

What makes the show so touching is its poignant undertow. Dietrich was a savvy artist. She understood how to craft a glamorous, exotic public persona, noting that a carefully constructed illusion could sustain a lucrative private reality.

Rendezvous With Marlene is inspired by a phone call between the two in 1988. Dietrich was living as a recluse in Paris; Lemper had just received the Molière Award for Cabaret. Dietrich became a star in 1928, thanks to The Blue Angel. Six days before Lemper played the same role 64 years later in Berlin, Dietrich died.

Lemper treasured their time together and her respect for Dietrich is evident in Rendezvous. The journey is biographical. She neatly charts Dietrich’s rise from cabaret singer to Hollywood star to her successful stage shows with music director Burt Bacharach with customary Lemper flair.

Ever the anti-Nazi, Dietrich secured American citizenship and entertained American soldiers in WW II. The Germans never forgave her, still calling her a traitor at her Berlin burial in 1992. Lemper sadly relates her homeland’s cruelty, while relaying Dietrich’s joys and sorrows in song, including Hollaender’s “The Ruins of Berlin.” Mercer’s “When The World Was Young” or Seeger’s “Where Have All The Flowers Gone?”

Capturing the essence of Dietrich’s voice, whether she’s discussing dinners with Billy Wilder, bisexuality or her movies, Lemper maintains her allure — and her mysterious aloofness. While there are moments that could be trimmed, overall, the experience is intimate and moving, the chance to watch a dazzling star channel another. — Fern Siegel

Bromance, now off-Broadway at the New Victory Theater, mixes breathtaking acrobatics and silent film-esque comedic bits. It also delivers a healthy serving of homoerotic innuendo into a one-hour show that can delight and astound.

The performers from Britain's Barely Methodical Troupe are magnetic and skilled. The three core members of Barely Methodical Troupe are Louis Gift, Charlie Wheeller and Beren D’Amico.

Barely out of circus school, they created Bromance. Along with three newer cast members, the troupe neatly blurs the line between dance and circus, eager to explore male relationships, starting with handshakes and moving to semi-nude embraces.

Some sequences are quite subtle and tender, if you understand the sexual/romantic themes at work. Little dramas of jealousy and attraction are played out, amid impressive acrobatics and dance moves.

In fairness, post-show, parents debated how much their children understood about what happened on stage.

Bromance — and the title says it all — is focused on pushing the limits of both aerial feats and what young audiences usually see. It’s beauty in motion, with a twist.

Though most of the more sexual elements probably fly over children's heads as easily as the performers do, they are evident throughout — from the use of paper swans as stand-ins for phallus size to Ton-Loc's "Wild Thing" as choice of music for a dance sequence.

Bottom line: It’s physically amazing, but thematically, it’s more adult than children’s fare.

— Fern Siegel

Why bother with endless FBI and Congressional investigations? Just call in Derren Brown. The British mentalist has an uncanny ability to determine if someone is telling the truth — and he’s big on the wow factor.

Early in “Derren Brown: Secret,” he admits to mining the “quirkier areas of psychology and the power of the perfectly placed lie.” He is skillful at illusion, but this isn’t traditional magic or sleight of hand.

What defines Brown is his dexterity and charm in mind reading. And he employs both to great effect.

Dapper in a brown three-piece suit — and later tie and tails — the

polished, confident Brown is making his American debut off-Broadway

at the Atlantic Theater’s Linda Gross Theater. He nails his

clairvoyance — and is so quick as a hypnotist — he keeps the

audience in the palm of his hand.

By keeping his patter neatly paced, he takes us on a magical

journey. But most unusual, he dismisses any psychic ability. Brown

is not divulging his secrets, aside from the fact he’s a smooth

entertainer.

One of the more memorable moments is his locked-box number, complete with a touching backstory. Another is the recreation of the oracle routine, made famous in the 1930s. He explains that several magicians who did the act went insane, which only builds excitement.

In short, it isn’t simply that Brown reveals audience thoughts or details — it’s the specificity that seduces the crowd. The script, written by Brown, Andy Nyman and Andrew O’Connor, both noted as directors, is smart, engaging and, at times, stunning.

"Secret" is a ticket to amazement that will stick with you long after you leave the theater.

Less amazing is “The Lucky One,” the 1924 play by A.A. Milne, revived by the Mint Theater and now at the Beckett on Theater Row. Most Americans know Milne as the author of Winnie-the-Pooh, but he also had a successful career as a playwright.

Here, the story addresses a well-to-do family and two sons. Gerald (Robert David Grant), a whiz in the Foreign Office and engaged to Pamela (Paton Ashbrook), and younger brother Bob (Ari Brand), drowning in an ill-suited financial career.

Throw in Tommy (Andrew Fallaize), a family friend, the kind of good-natured goof who populated P.G. Wodehouse’s Drone’s Club, and his equally ditzy girlfriend Letty (Mia Hutchinson-Shaw), and you get the picture.

The underlying thrust — that people aren’t always what they seem — is a solid premise. It’s also the ironic title; good cheer can hide a multitude of grievances. British men of a certain era specialized in hiding their emotional selves, so the dramatic revelation has to ring true.

A light touch can sustain a serious point, but there is a difference between light and slight. The second act is stronger, but the overall brittleness remains. That’s no fault of the cast, who uniformly delivers, including Cynthia Harris as the intuitive great-aunt.In this particular instance, however, slight trumps all. The breezy dialogue, reminiscent of the era, seems to upend Milne’s larger message. —Fern Siegel

The title suggests an homage to the swing era, but the new Broadway musical "Bandstand" at the Bernard Jacobs is more nuanced. It addresses the pain of returning WWII vets in 1945.

It underscores, much like "The Best Years Of Our Lives" film, that the public doesn’t fully comprehend what these men endured or the horrors they witnessed.

And that’s a worthy subject.

"Bandstand" is seemingly two stories: post-war realities and present-day necessities, wrapped in the seductive sounds of swing.

These former soldiers are also musicians eager to establish themselves. Led by Danny Novitski (a strong Corey Cott), whose ambition and upbeat attitude is a poster for can-do Americanism, he puts together a band of vets.

He also copes with his own demons, which force him to visit Julia (Laura Osnes), the widow of his best friend, who died in action in the Pacific. Indeed, each band member wrestles with emotional and physical wounds: Davy on bass (Brandon J. Ellis), Johnny on drums (Joe Carroll), Nick on trumpet (Alex Bender), Wayne on trombone (Geoff Packard) and Jimmy on sax (James Nathan Hopkins).

In our era, where veteran acknowledgement is relegated to a quick “thanks for your service,” the men of "Bandstand" are a stark reminder of harsher truths.

Eager to move forward, Danny has a single goal — propel his band to the top. Julia, who happens to be a nifty poet/lyricist with powerful singing chops, wants only to be left alone. This being a musical, they will join forces for some fantastic music, thanks to Broadway newcomers Richard Oberacker and Rob Taylor, and electric dance numbers by director-choreographer Andy Blankenbuehler, who won the Tony for Hamilton.

In fact, "Bandstand" makes a strong argument

for the healing power of music.

Osnos and Cott deliver appealing and engaging performances. The

story is touching, but cutting 10-15 minutes would tighten the pace

and excise some of the cheaper bits, like the play on Julia’s last

name, Trojan.

There is a dark undertow here that could be a show all its own. But like the musicals of the Forties, the kinetic "Bandstand" ends on a high note.

"Anastasia" at the Broadhurst also pushes for a happy ending, but from a mythical plane. The Broadway musical is inspired by the 1997 animated film and the 1956 Hollywood movie. So suspend belief and make room for some exquisite projection designs from Aaron Rhyne and costumes from Linda Cho.

The often-sumptuous "Anastasia" is an eye-popper. The politics are another story.

The plot is well-known: The Bolsheviks slaughtered Czar Nicholas II’s family when seizing power in 1917. But because not all the bodies were recovered, a story arose — for decades — that young Anastasia escaped with the help of a sympathetic guard.

Fast-forward to 1927. A handsome street

hustler Dmitry (Derek Klena) and aristocratic imposter Vlad (John

Bolton) hatch a plan, common during the era. They will transform

street urchin Anya (Christy Altomare) into Anastasia, the lost

Romanov princess.

Once styled, they flee to Paris, hoping to convince the royal

grandmother (Mary Beth Peil) that Anya is the real deal. That is, if

they can escape Gleb (a nuanced Ramin Karimloo), the Bolshevik hot

on Anya’s trail. The Soviets want to eradicate any reminder of

imperial glory threatening their new order.

Stephen Flaherty and Lynn Ahrens adapted their movie score to the stage. New pop melodies have been added to the Terrance McNally book, which mixes adventure and nostalgia in equal measure.

Altomare is excellent as the beautiful and independent Anya, a young girl surviving a tumultuous world. Klena and Bolton are ideal comrades in this romance/history tale slickly directed by Darko Tresnjak, who won a Tony for “A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder.”

In fairness, however, imperial rule should not be heralded or mourned. One brief aside — the Czar left his people with nothing — is the only acknowledgement of Romanov brutality. Anastasia is a lovely musical that magically eliminates any White Russian unpleasantness, focusing on the assumed fraud — or is it? — of Anya’s identity.

The story, like the politics, is simplistic. But as fairy tale, the songs and entertaining performances click.

—Fern Siegel

Beauty is serious business.

“There are no ugly women, only lazy ones,” decreed the remarkable Helena Rubinstein, played with elegance and moxie by the formidable Patti Lupone.

Rubinstein, who pioneered the science of beauty, as well as brand marketing, commands all eyes in the new Broadway musical War Paint, which details her rivalry with fellow cosmetics titan Elizabeth Arden (Christine Ebersole).

While the premise might sound like a classy catfight, in truth, the rivalry fuels their competitive edge. Corporate espionage is child’s play to these two. They endure betrayals, social change, shifting demographics and loneliness with practiced élan.

In fairness, War Paint, now at the Nederlander, is more reportage than theatrics, biography rather than drama. The production is written by Doug Wright for two talented divas — each owns dual Tonys. So while the show lacks dramatic tension — it’s still a pleasure to watch these Broadway giants on stage, who refuse to refer to each other by name.

They are accompanied by the music/lyrics of Scott Frankel and Michael Korie. (Frankel and Wright were Tony-nominated for Grey Gardens, with lyrics by Korie.)

Both women are self-creations — Arden is far more antiseptic and brittle, casual with her anti-Semitism and class snobbery. Of Estee Lauder, she sneers: “Esther from Queens!” Her pink packaging covers her world in gauze of hyper-femininity, but it can’t disguise the disquiet of WASP exclusion.

Conversely, Rubinstein, the first self-made female millionaire, is acutely aware of the anti-Jewish sentiment of New York’s upper-crust. A collector of modern art and a noted philanthropist, she escaped a dreary life in Kracow, Poland, to build an empire. Her business rival prefers racehorses.

(Madam C.J. Walker, who built a beauty and hair-care empire for African-American women, was credited with being wealthiest African American woman in the U.S. on her death in 1919.)

The play casually mentions Rubinstein’s study in Europe, but she studied with experts to learn about skin treatments and dietary practices. Proficient in herbal preparations, using lanolin in Australia, where she began her ascent, she parlayed that knowledge and clever marketing into “A Day of Beauty” at the Helena Rubinstein salons, which became popular worldwide.

Arden, real name Florence Graham, was credited with making makeup socially acceptable; she was noted for handing out red lipstick to suffragettes. (Previously, only actresses or prostitutes used it.)

Together, they dominated the beauty business. En route, they contend with oily Charles Revson (Erik Liberman), Arden’s husband Tommy (John Dossett) and Rubinstein’s associate Harry (Douglas Sills.) While the men are capricious, the women keep their eyes on the prize.

Zipping through a 30-year period from the 1930s to the 1960s, War Paint offers eye-popping costumes by Catherine Zuber. Lupone’s Rubinstein, who adored hats and big jewelry, is a standout every time she steps on stage. David Korin’s sets maintain a luxe edge.The versatile leads deliver the goods, replicating the rivalry and bitterness between the powerhouses with sass and sensibility. The chic War Paint proves beauty carries a high price — in all realms. But the joy is watching Lupone and Ebersole, representing such notable women, put their best face forward.

—Fern Siegel

Miss Saigon

It’s back – and it’s as brassy as ever.

The revival of Miss Saigon, now at the Broadway Theater, centers on prostitution and the exploitation of women to underscore its thematic concerns. War is hell — and women are often the eternal victims of political fallout.

It’s been more than 16 years since Cameron Mackintosh’s Miss Saigon was in New York — and audiences who loved the operatic elements will be enticed anew by this production. And yes, its famed helicopter is a high point.

The musical opens in Saigon in 1975, in the last days of the Vietnam War.

Life is cheap. The American GIs treat women like dirt, as does the half-French, half-Vietnamese Engineer (an excellent Jon Jon Briones), who owns the nightclub patronized by the U.S. Army. Sleazy and violent, the Engineer caters to anything the young soldiers desire.

Yet amid turmoil, Chris (Alistair Brammer) and Kim (Eva Noblezada) fall passionately in love. Their on-stage chemistry is explosive, an apt backdrop to underscore the insanity that engulfs them. That includes the ominous Thuy (Devin Ilaw), Kim’s cousin, who comes to Saigon to claim her.

Despite the best-laid plans, Chris is forced

to abandon Kim — setting in motion an onslaught of guilt, terror and

violence that will haunt them both.

This incarnation boasts a solid cast; they fully capture the

heartbreak and horror of those caught in the crosshairs of war.

Briones, who starred in the recent London revival, has nailed the oily, conniving hustler, notably in his big number “The American Dream,” while Noblezada’s debut is impressive. Bob Avian’s musical staging is raw and engaging, and the Boubil/Schonberg score remains as entertaining as ever. —Fern Siegel

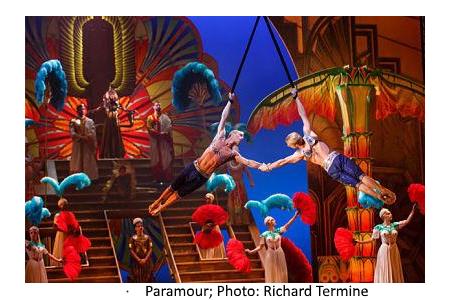

Paramour at the Lyric Theater is a departure for Cirque du Soleil: The acrobatic brilliance remains, but it’s coupled with the Broadway musical genre, set in Hollywood’s golden age.

The story is a love triangle — Hollywood director A.J. (Jeremy Kushnier) plucks Indigo (Ruby Lewis) from obscurity to turn her into a star. Her composer partner beau Joey (Ryan Vona), isn’t amused.

In between the predictable plot lines, the $25 million production offers inventive stage acts. At a speakeasy, waiters perform nifty turns. There’s always some Cirque-style business mixed with various scenes, like the stunning high-wire act from the Atherton twins. Most of the visual elements, coupled with an ample use of video projects, are dazzling.

Director-conceiver Philippe Decoufle keeps the action flowing, and every now and then, the stage performances and the romance connect. One of the best moments is the “Love Triangle,” where a trio of dancers recreate the emotional tug-of-war in mid-air. There’s even a comic-book-style finale chase scene that’s terrific to watch — and a bit reminiscent of Spider-Man: Turn Off The Dark, which also played the Lyric.

The twist, and the downside, is the story itself, which is banal. That doesn’t mean the show isn’t entertaining — or the leads don’t deliver. Just that as Broadway musicals go, it’s more Las Vegas than Great White Way.

- Fern Siegel

It’s 1959 Eisenhower America, a fancy prep school in New England. The headmaster is smug, the kids range between privileged and awkward — and authority rules.

Then a small miracle happens.

English teacher Mr. Keating (a wonderful Jason Sudelkis) arrives, proof that words elevate and ideas can change the world. He reminds the boys to “gather ye rose-buds while ye may,” captivating them with the power and passion of poetry.

And suddenly, the spark ignites.

Dead Poets Society, now off-Broadway at CSC,

is a beautifully rendered production, deftly directed with elegance

— and without sentimentality — by John Doyle. The boys come alive —

and despite their adolescent angst — discover beauty and depth.

Which sounds ideal — if their world wasn’t run by pompous,

authoritarian figures. Culture and sensibility are anathema to them.

And a clash is inevitable.

Keating pushes the boys to open their minds

and hearts in an era when conformity and anti-intellectualism rule.

Oscar winner Tom Schulman adapted his screenplay, and it has added

resonance in such an intimate setting. We feel the boys’ longings,

much as we absorb the larger ethos: That the humanities can enhance

your life is a valuable message; one that seems critically

importance today.

Doyle keeps his production lean, using books for desks and getting

excellent performances from a strong ensemble cast that doesn’t miss

a beat: Zane Pais, Thomas Mann, Cody Kostro, William Hochman, Yaron

Lotan, Bubba Weiler, David Garrison, Stephen Barker Turner and

Francesca Carpanini.

In Trump-era America, the play is a timely reminder of how dangerous rigidity and insensitivity can be. But Dead Poets Society is also a battle cry, encouraging us to embrace the words of Tennyson: “To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

-Fern Siegel